Dear Daughters,

Here in our part of the world, it was the second or third week of Lent last year that everything shut down. Back then, we paused life for what we thought was two weeks. We had hopes, even if we knew they were long shots, of gathering as a church family on Easter morning.

It didn’t happen as we had hoped. Obviously.

And so we’ve learned, when we have been at our best, to hold our hopes lightly this last year. We’ve also learned to grieve losses.

It sure has been a year of grieving, though, and it isn’t lost on me that the year of grief began during a season we kicked off with ashes on our foreheads.

I would say that is irony, but I think it’s more like a parable than anything else.

Last year, I held in my hands the small container of ash during our Ash Wednesday service as my faith community came up one by one and dipped their fingers into the black soot. I watched up close as each person turned to the loved one next in line and imposed the ashes on his or her forehead. I heard each person tell a spouse, or child, or friend, “From dust you came. To dust you will return.”

From dust you came. To dust you will return.

It would be an understatement to say I cried through the whole ritual.

Last year, long before I had any concept of five hundred thousand American deaths, I wrote about the season being the “Lentiest” Lent I’d known. I remember telling others that it might end up being the Lentiest Lent of our entire lives.

The Lentiest.

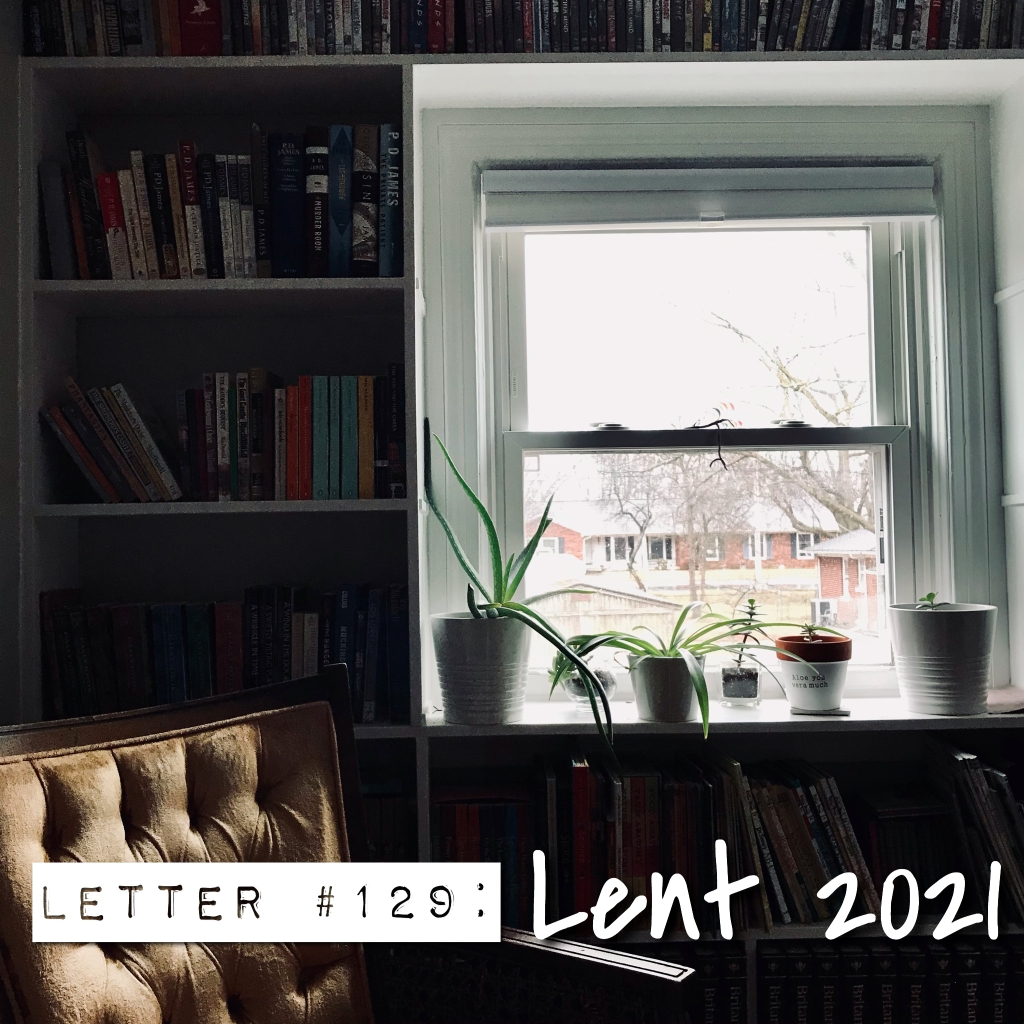

And now here we are: a whole liturgical year later, the needle on our wooden Calendar pointing to the second Sunday of Lent.

Though many people I know are reluctant to approach Lenten practices this year at all–haven’t we given up enough? they ask. Haven’t we been reminded for an entire year of what it means to sacrifice?—I’ve found myself leaning into Lent.

I’ve been reframing it in my head and in my heart, considering what it means that our days here in the northern hemisphere lengthen during this season. That’s where the word “Lent” comes from after all.

I’m remembering that this season teaches us that ashes are nourishing, that ash amends the soil. We burn last year’s palms to make this year’s ash, but on Palm Sunday, we get to be reminded that only God can do the miraculous opposite: turn the ash into palms.

The ash reminds us, all season long, that something is left after the burning.

Something remains.

Lent, if practiced well, doesn’t simply remind us through our fasting and disciplines and floundering of our fallen humanity: our brokenness, our undeservedness of love, our need of a savior. Sure, it does that, too, but that’s not the full story. Maybe not even the most important part of The Story.

No, Lent is Good News.

Lent shows us what love is, so we can recognize it.

And what’s more: Lent asks us to open up our hands, so we can receive it.

Girls, I have a friend who says, “I’ve been to the bottom, and I know it’s solid.”

That’s something you can say after a season of grief. It’s hard to voice those words right in the middle of it.

I do think it has been the Lentiest of years, but I think that might be precisely why, if we open our palms to hold the ash lightly, we might find ourselves in a good position to recognize Love.

It’s solid.

Love,

Your Momma